By Ed Staskus

It was sometime during the Me Decade that I discovered I was poor as a church mouse. I owned lots of dog-eared books, some clothes, and a car I didn’t dare drive. I didn’t own an alarm clock. I didn’t have any money in the bank because I didn’t have a bank account. I was living at the Plaza Apartments on Prospect Ave., where the rent was more than reasonable. I got by doing odd jobs and taking advantage of opportunities, although I was far from being a capitalist.

The Plaza was in a neighborhood called Upper Prospect. There were about thirty architecturally and historically significant buildings there, built between 1838 and 1929. The Plaza was one of the buildings. Upper Prospect had long benefitted from Ohio’s first streetcar line that connected it to the downtown business district. Those days were long gone.

In the 1870s Prospect Ave. advanced past Erie St., which is now E. 9th St., and kept going until it reached E. 55th St. That’s where it stopped. “Lower Prospect, closer into downtown, went commercial long ago, but Upper Prospect stayed residential longer,” says Bill Barrow, historian at the Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University. Lower Prospect is where lots of downtown entertainment is now, including Rocket Arena, where the Cleveland Cavs follow the bouncing ball, and the House of Blues, where music fans have a ball.

The Winton Hotel was built in 1916 on the far side of E. 9th St. It was nothing if not grand. It was renamed the Carter Hotel in 1931, suffered a major fire in the 1960s, but was renovated and renamed Carter Manor. I never set foot in it. The Ohio Bell Building went up in the 1920s before the Terminal Tower on Public Square was built. When it was finished it became the tallest structure in the city. I never set foot in it, either. It was the building that Cleveland’s teenaged creators of Superman had the Man of Steel leap over in a single bound. The cartoon strip first appeared in their Glenville High School student newspaper, which was the Daily Planet.

Before Superman ever got his nickname, the first Man of Steel was Doc Savage. There were dozens of the adventure books written by Lester Dent. When I was a child I read every one I could get my hands on. Doc Savage always saved the day. Nothing ever slowed him down, not kryptonite, not anything.

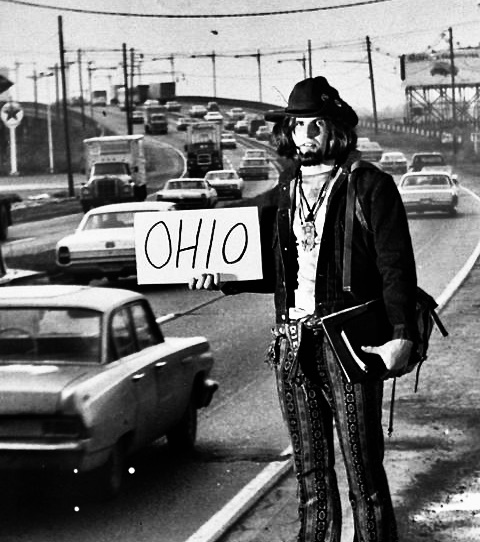

In the 1970s Prospect Ave. wasn’t a place where anybody wanted to raise children. Nobody even wanted to visit the place with their children in tow. The street was littered with trash, dive bars, hookers, and bookstores like the Blue Bijou. There was heroin in the shadows and plasma centers that opened first thing in the morning. The junkies knew all about needles and got paid in cash for their plasma donations.

The Plaza was around 70 years old when I moved in. There was ivy on the brick walls and shade trees in the courtyard. There were day laborers, retirees, college students, latter day beatniks, scruffy hippies, artists, musicians, and some no-goods living there. “The people who lived in the building during my days there helped shaped my artistic and moral being,” Joanie Deveney said. “We drank and partied, but our endeavors were true, sincere, and full of learning.” Everybody called her Joan of Art.

Not everybody was an artist or musician. “But anybody could try to be,” Rich Clark said. “We were bartenders and beauticians and bookstore clerks with something to say. There was an abiding respect for self-expression. We encouraged each other to try new things and people dabbled in different forms. Poets painted, painters made music, and musicians wrote fiction.”

The avant-garage band Pere Ubu called it home. Their synch player Allen Ravenstine owned the building with his partner Dave Bloomquist. “I was a kid from the suburbs,” Allen said. “When we bought the building in the red-light district in 1969, we did everything from paint to carpentry. We tried to restore it unit by unit.”

The restoration work went on during the day. The parties went on during the night. They went on long into the night. “I remember coming home at four in the morning,” Larry Collins said. “There would be people in the courtyard drinking beer and playing music. We watched the hookers and the customers play hide-and-seek with undercover vice cops. In the morning, I would wake up to see a huge line of locals waiting in line in front of the plasma center.”

When I lived there, I attended Cleveland State University on and off, stayed fit by walking since my car was unfit, and hung around with my friends. Most of us didn’t have TV’s. We entertained ourselves. I worked for Minuteman whenever I absolutely had to. The jobs I got through them were the lowest-paying worse jobs on the face of the planet, but beggars can’t be choosers.

I spent a couple of weeks on pest control, crawling into and out of tight spaces searching for rats, roaches, and termites. My job was to kill them with poison. The bugs ran and hid when they saw me coming. I tried to not breathe in the white mist. I spent a couple of days roofing, hoping to not fall off sloping elevated surfaces that were far hotter than the reported temperature of the day. The work was mostly unskilled, which suited me, but I got to hate high places. My land legs were what kept me upright. I didn’t want to fall off a roof and break either one of them

I passed the day one summer day jack hammering, quitting near the end of my shift. I thought the jack hammer was trying to kill me. “If you don’t go back, don’t bother coming back here,” the Minuteman boss told me. “Take a hike, pal,” I said, walking out. I wasn’t worried about alienating the temporary labor agency. Somebody was always hiring somebody to do the dirty work.

The Plaza was four stories tall and a basement below, a high and low world. Some of the residents were lazy as bags of baloney while others were hard-working. Some didn’t think farther ahead than their next breath while others thought life was a Lego world for the making. There was plenty in sight to catch one’s eye.

“I had a basement apartment in the front,” Nancy Prudic said. “The junkies sat on the ledge and partied all night long. But the Plaza was a confluence of creative minds from many fields. It was our own little world. Besides artists, there were architects and urban planners.”

Pete Laughner was a hard-working musician. He was from Bay Village, an upper middle class suburb west of Cleveland. He wrote songs, sang, and played guitar. He was “the single biggest catalyst in the birth of Cleveland’s alternative rock scene in the mid-1970s,” Richard Unterberger said. He led the bands Friction and Cinderella Backstreet. He co-founded Rocket from the Tombs. “They were a mutant papa to punk rock as well as spawning a number of famous and infamous talents, all packed into one band,” Dave Thomas said. After the Rockets crashed and burned, Pete teamed with Dave to form Pere Ubu.

Dave Thomas was nicknamed the Crocus Behemoth because he was ornery and overweight. He went against the grain by occasionally performing in a suit. He was a tenor who sometimes sang and others times muttered, whistled, and barked. “If nobody likes what you do, and nobody is ever going to like what you do, and you’ll never be seen by anyone, you do what you want to do,” he said. He commandeered the street in front of the Plaza for middle of the day open air concerts. “He never let the lack of any musical training get in his way,” said Tony Maimone, Pere Ubu’s bass player.

Pere Ubu’s debut pay-to-get-in show was at the Viking Saloon in late 1975. Their flyer said, “New Year’s Eve at the Viking. Another Go-damn Night. Another year for me and you, another year with nothing to do.” Pete had a different take on it. “We’re pointing toward the music of the 80s.”

When he wasn’t making his stand on a riser, Pete was writing about rock and roll for Creem, a new monthly music magazine which was as sincere and irreverent as his guitar playing. The magazine coined the term “punk rock” in 1971. “Creem nailed it in a way that nobody else did,” said Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth.

Pete played with the Mr. Stress Blues Band in 1972 when he was 20 years old. They played every Friday and Saturday at the Brick Cottage. Mr. Stress called the squat building at Euclid Ave. and Ford Rd. the “Sick Brick.” When he did everybody called for another round. Monique, the one and only bartender, ran around like a madwoman. “The more you drink, the better we sound,” Mr. Stress said and picked up his mouth organ.

The harmonica man was a TV repairman by day. The lanky Pete was in disrepair both day and night. He wasn’t a part-time anything. He wasn’t like other sidemen. His guitar playing was raw and jagged. While the band was doing one thing, he seemed to be doing another thing.

“He only ever had three guitar lessons,” his mother said. Pete was in bands by his mid-teens. “He was my boyfriend when we were 15,” Kathy Hudson said. “He still had his braces. He was with the Fifth Edition. They were playing at the Bay Way one time and he wanted them to bust up their equipment like The Who. The others weren’t down with it.”

“He was so energetic and driven, but his energy couldn’t be regulated,” said Schmidt Horning, who played in the Akron band Chi Pig. “It could make it hard to play with him. He was so anxious and wouldn’t take a methodical approach.”

Charlotte Pressler was the woman Pete married. “From 1968 to 1975 a small group of people were evolving styles of music that would, much later, come to be called ‘New Wave’. But the whole system of New Wave interconnections which made it possible for every second person on Manhattan’s Lower East Side to become a star did not exist in Cleveland,” she said. “There were no stars in Cleveland. Nobody cared what they were doing. If they did anything at all, they did it for themselves. They adapted to those conditions in different ways. Some are famous. Some are still struggling. One is dead, my Pete.”

Not long before everything fell apart Pete stepped into a photo booth in the Cleveland Arcade, one of the earliest indoor shopping arcades in the United States. He was wearing a black leather jacket and looked exhausted. His eyes had the life of broken glass in them. He sent the pictures and a note to a friend. “Having a wonderful time. Hope you never find yourself here.”

He played his kind of music at Pirate’s Cove in the Flats, along with Devo and the Dead Boys. “We’re trying to go beyond those bands like the James Gang and the Raspberries, drawing on the industrial energy here,” Pete said. He played at the Viking Saloon, not far from the Greyhound station, until it burned down in 1976. Dave Thomas was a bouncer there, keeping law and order more than just an idle threat. He wasn’t the Crocus Behemoth for nothing.

“I’m drinking myself to death,” Pete wrote to a friend of his in 1976. “No band, no job, running out of friends. It’s easy, you start upon waking with Bloody Mary’s and beer, then progress through the afternoon to martinis, and finally cognac or Pernod. When I decided I wanted to quit I simply bought a lot of speed and took it and then drank only about a case of beer a day, until one day I woke up and knew something was wrong, very wrong. I couldn’t drink. I couldn’t eat. And then the pain started, slowly like a rat eating at my guts until I couldn’t stand it anymore and was admitted to the hospital.”

The rat was pancreatitis. If you lose a shoe at midnight you’re drunk. Pete lost shoes like other people lost socks in the dryer. He didn’t need any shoes however, where he was going. It was the beginning of the end of him. It didn’t take long. He wouldn’t or couldn’t listen to his doctor’s orders. He went back to his old pal, which was booze.

“Pete could do whatever he wanted to do,” said Tony Mamione. “He was instrumental in crafting the Pere Ubu sound, but, even at such an early age, had a deep understanding of all kinds of music.” Tony and Pete met when they lived across the hall from each other on the third floor of the Plaza Apartments. “I had just moved in and would play my bass and Pete heard it through the walls and knocked on my door. We started talking and he went back and grabbed his guitar and some beer, and we started jamming right away.”

Pete was as good if not better on the piano than the guitar, even though the guitar was his tried and true. One day he found a serviceable piano at a bargain price and bought it. He and Tony picked it up to take back to the Plaza. “Here I was driving his green Chevy van down Cedar Ave. and there he was in the back of the van rocking out on the piano,” Tony said. “He was so special, a pure musician.” After they dragged, muscled, and coaxed the piano up to the third floor, they had some beers and the next jam session started.

“I want to do for Cleveland what Brian Wilson did for California and Lou Reed did for New York,” Pete said in 1974. “I’m the guy between the Fender and the Gibson. I want a crowd that knows a little bit of the difference between the sky and the street. It’s all those kids out there standing at the bar, talking trash, waiting for an anthem.”

They would have to wait for somebody else. Pete Laughner died in 1977 a month before his 25th birthday. He was one year younger than me when he met his maker. He didn’t die at the Plaza Apartments. Neither of us was there anymore. He died in his sleep at his parent’s home in Bay Village. There’s nowhere to fall when your back is against the wall, except maybe where you got up on your feet in the first place.

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Atlantic Canada http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com.

“Ebb Tide” by Ed Staskus

“A thriller in the Maritimes, magic realism, a double cross, and a memory.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Available at Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CV9MRG55

Summer, 1989. A small town on Prince Edward Island. Mob money on the move gone missing. Two hired guns from Montreal. A peace officer working the back roads stands in the way.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication