By Ed Staskus

When I moved from the near east side of downtown Cleveland to Carpenter, Ohio the post office there had been gone more than ten years. The Baptist church was still standing, but the minister didn’t live in the whistle-stop. He drove in on Sundays, performed his mission, and drove away after shaking a few hands. I went to the service one morning, but the minister looked like the talent scout for a graveyard, and it was the last time I went. The general store had closed even before the post office, which was good for Virginia Sustarsic and me, because that is what we moved into, staying the spring summer and into the early fall.

The post office was opened in 1883 and stayed there until 1963. Nobody knew who the town was named for, although three men who had been natives of the place took credit. There was Amos Carpenter, an old geezer who talked too much, Jesse Carpenter, a farmer who hardly ever talked, and State Senator J. L. Carpenter, who only talked when it counted. He brought tracks and a railroad station to the town. Those were long gone, too.

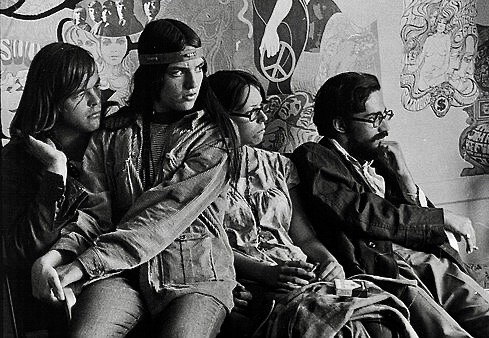

It wasn’t my idea to go live local yokel on the banks of Leading Creek, but Virginia argued living in the country was the way to go. She was a hippie and wore its ethos of going back to the roots on her sleeve. I countered that the hippies happened in coastal cities like San Francisco and New York, flowered in college towns like Austin and Ann Arbor, and were trucking along in cities like Omaha, Atlanta, and Cleveland. We were both from Cleveland, born of immigrant stock, she Slovenian and me Lithuanian.

My reasoning fell on deaf ears.

A friend of ours with a van drove us and our stuff to Carpenter, dropped us off, and waved goodbye. I had never been there before. Virginia had been there twice, having a friend who lived in that neck of the woods. It took less than ten seconds to look the town over. There wasn’t much to see. We stashed everything away in the sturdy but dilapidated 19th century-era store and walked up Carpenter Hill Rd. to Five Mile Run, detouring down what passed for a driveway to a small house where Virginia’s friend and his bloodhound lived.

He was somewhere between not young and middle-aged, lean and scraggly, literate and friendly. He was the kind of man who was a hippie long before there were hippies. He read lots of books and smoked lots of weed. There was a Colt cap and ball pistol on his coffee table, laying there as relaxed as could be. It was a Walker .44. It was big, old as dirt, spic-n-span workable.

“That’s an imposing handgun,” I said.

“They call it the Peacemaker,” he said. “Even though it can get you into a load of trouble the same as not. I call it the Devil’s Right Hand.”

He shot rabbits with it for his stew pot. The large percussion revolver could have taken deer in season. He let me shoot it at a tree later that summer. It was heavy when I lifted it. I shot it stiff-armed expecting more recoil, which turned out to be modest. What I didn’t expect was the “BOOM!” at the end of my arm. I was glad I missed the tree. Even though it was a full-grown maple the ball hitting it might have put it on the woodpile.

We spent a week sweeping dusting cleaning arranging the ground floor front room of the general store. There were two storerooms in the back and an upstairs we didn’t mess with. Two long broad oak tables served as platforms for working and preparing food. We ate in rocking chairs we set up at one of the windows. We found a braided round rug in a closet, beat the hell out of it, and rolled it out in the middle of the floor.

After laying in a garden, we stuck a scarecrow of Grace Slick on a stick to guard the plot. The scarecrow, however, fell down on the job. Birds shat on her and rabbits ran riot. We ended up hunting and gathering.

A kitten walked in out of the blue one morning, worn out and hungry as a horse. He was white with a black blob on his chest and a masked face. Virginia gave it a bowl of water, but we didn’t have cat food. “We should go into town, get some, and some food for us, too,” I said.

Virginia was a genius at living off the land, but we still needed some store-bought stuff, salt pepper coffee pasta peanut butter and pancake mix, as well as toilet paper. The outhouse was bad enough without the comfort of Charmin.

There were two municipalities within driving distance, Athens, which was 15 miles northeast of us, and Pomeroy, which was 17 miles southeast. Ohio University was in Athens, had several grocery stores, and plenty of citizens our own age. Pomeroy was on the Ohio River, was notorious for being repeatedly destroyed, and there was nobody our age there. We never went to Pomeroy except once to look around.

The town was consumed by fire in 1851, 1856, 1884, and 1927. The floods of 1884, 1913, and 1937 were even more disastrous. 1884 was an especially bad year, what with fire and flood both. Why the residents kept rebuilding the place was beyond us, although we speculated they must have been plain stubborn.

We stopped at the courthouse to lay eyes on the excitement. We had read in “Ripley’s Believe or Not!” that there is a ground floor entrance to each of its three stories, the only one of its kind in the world The sight of the phenomenon wasn’t all that exciting. A plaque explaining that the courthouse served as a jail for more than 200 of Morgan’s Raiders after their capture in the Battle of Buffington Island during the Civil War caught our attention. It was exciting to learn that Ohio boys had gotten the better of Johnny Reb when they ventured north.

The county seat of Meigs County is mentioned in Ripley’s a second time for not having any cross streets. We took a stroll and didn’t see any. It didn’t seem deserving of mention in Ripley’s, but what did we know?

Once he had a steady supply of food, out kitten got better and bigger. He spent his days outside and after sunset inside. He learned fast there were plenty of hungry owls, racoons, and coyotes in the dark. At first, when he was a tyke, he slept on top of my head at night. As he grew, I had to move him to the side. It was like wearing a Davey Crocket racoon hat to bed.

Meigs County, in which Carpenter lay, is 433 square miles with a population of around 20,000, or 54 people per square mile. Where we came from, Cuyahoga County, it was more like 3,000 people per square mile. At night in the middle of Meigs County it often seemed like 2 people per square mile, Virginia and me.

There wasn’t much crime in the county, thank goodness, because the law enforcement amounted to one sheriff, one lieutenant, one sergeant, and six deputies. We had been in town a week-or-so when the sheriff stopped by to say hello. He was a pot-bellied man with fly belly blue eyes. He made sure we had the cop and fire department phone numbers even though we didn’t have a phone. He warned us not to mess around with the marijuana market. Virginia made roach clips for sale in head shops, but only smoked so much, and said so.

“No, I don’t mean that girlie,” he said. “I don’t care what you do on your own time. What I mean is, don’t mess with the growers. They’ve got it tucked in all around here. Some of them have been to Vietnam and back, and they learned a thing or two from Charlie. Even the DEA is careful when they chopper around these hills spraying their crop.”

He pronounced Vietnam like scram.

Meigs County is on the Allegheny Plateau. It is especially hilly where we were. The soil isn’t the greatest. The top crop by far is forage, followed by soybeans and corn. Layers and cattle are the top livestock. The marijuana growers hid their fruitage in corn fields, where it was hard to spot.

Moonshine was made from the first day Meigs County was settled, for themselves and for whenever a farmer needed hard cash in a hurry, as long as they were near water and could haul a barrel of yeast and a hundred feet of copper line to the still. The yeast is stirred with sugar and cracked corn until it ripens. When the mash is ready it’s poured into an airtight still and heated. When it vaporizes it spirals through copper pipes, is shocked by cold water, returns to its original liquid form, and drips into a collection barrel.

After that it is ready to go and all anyone needed was a fast Dodge to get it to market.

The marijuana growers were mostly young, a loose-knit group known as the Meigs County Varmits, which was also the name of their championship softball team. They drove Chevy and Ford pick-ups. They stopped by and said hello, just like the sheriff. One of them told us to keep our heads down the middle of October.

“What’s that all about?” I asked.

“That’s when we harvest our green and that’s when the state cops and Feds get busy. You’ll see their cars and spotter planes. They ask you any questions, play dumb. You hear any noise, ignore it.”

They had a hide-out in the woods where they had private stoner parties. Hardly anybody knew where it was, although everybody called it Desolation Row. It was some bench car seats thrown down on the ground and a rude shelter.

Meigs County Gold was high quality highly sought weed. It was the strain of choice for the Grateful Dead and Willie Nelson when they toured Ohio and West Virginia. Meigs County folk learned to not lock their cars and to keep their windows partly rolled down when they went to the Ohio State Fairgrounds in Columbus or Kings Island near Cincinnati.

When I asked why, a man said, “Because people see the Meigs County tag and it’s almost for sure you’ll have busted windows if you don’t. They will be looking for your pot.”

Our pots and pans were always filled with grub Virginia gleaned in the forest lands where she found nuts greens fruits and tubers. She collected walnuts chestnuts papaws raspberries blueberries and strawberries. She dressed up salads with dandelions fiddleheads and cattails. In the late summer she hunted for ginseng, selling it to a health food store in Athens.

She kept two goats in a shed. I fed them and cleaned up after them. They were more trouble than they were worth, especially after one of them head butted the minister who walked over late one Sunday morning inquiring about my spiritual frame of mind. The goat lowered his head and got him from behind, in the butt, knocking him down. He scuffed up his hands breaking his fall and got mad as the devil. He told the sheriff about it and the sheriff had to stop by and warn us to keep our goats civil.

“Yes, sir,” I said.

Carpenter was the kind of place where tomorrow wasn’t any different than a week ago. But it had its moments. A week-or-so after the sheriff paid us his official visit, we watched him drive slowly past our grocery store summer home on State Route 143 dragging an upright piano on rollers behind him, chained to his rear bumper. A deputy was walking beside the piano trying to keep it from falling over. It looked like a bad idea on the way to going wrong. We waved but didn’t ask any questions.

Our nearest neighbor was Jack, his two brothers, and their mother, on the other side of Leading Creek, a quarter mile down the state route. Velma looked like she could have been their grandmother, but Jack Jerome and Jesse called her mam. It was a one-story house with a front porch. They had running water and a bathroom, but no cooking stove or furnace. Velma did the cooking in the fireplace and they heated the house with the fireplace and a cast-iron potbelly stove. It was more than we had, which was just the potbelly thing.

“Food cooked in a fireplace tastes better than food cooked any other way, including charcoal grills,” Velma said. It was big talk, but she backed it up. She might not have been able to whip up a cake or a souffle, but she made just about everything else. We never turned down an invitation to dinner.

There were always half-dozen-or-more barely alive cars and trucks in their backyard, which was more like a field. There was a chicken house and a pen for pigs. They slaughtered and smoked their own pork. There was a big deep pond near enough to the house and they let us go floating and swimming in it whenever we wanted. They had an arsenal of rifles and shotguns, even though they didn’t mess around with marijuana. Moonshine might have been a different matter.

“How come you’ve got all those guns?” I asked Jack.

“That’s how our daddy raised us,” he said.

They were born and bred right there. The folks in the ranch-style houses up Carpenter Hill Rd. avoided them. Sometimes when we went swimming the sheriff’s car was there. I had the impression he wasn’t there on lawman business, but rather visiting.

By the end of summer, we realized we couldn’t stay. The Velma family already had enough cords of dried wood beside their house to keep themselves warm if winter went Siberian in Ohio. We didn’t even have a pile of twigs. We could have ordered coal, which was plentiful, but neither of us had ever started and stoked a coal furnace. We didn’t know anything about air vents. All we knew was dial-up thermostats for gas furnaces.

Our friend returned with his van and helped us move back to the Plaza Apartment in Cleveland. Prospect Avenue was the Wild West, but winter was coming, and it would be quiet for a while. We wouldn’t need a Peacemaker. We said goodbye to Virginia’s hippie friend and his bloodhound, and to Jack up the hill. Jerome and Jesse had gone hunting waterfowl, the first day for it. Velma gave us an apple pie for the drive home.

The cat, who was left-handed and so went by Lefty, decided to stay. He wasn’t a city boy. He wouldn’t have been able to make sense of the Cuyahoga River catching fire. Lefty had made friends with all the cats and dogs a half-mile in every direction, knew how to sneak into the grocery store closed doors or no doors, and had grown up enough to take care of himself. We slit open the 20-pound cat food bag and opened it like a book. We left it on the floor so he and his friends could have a party.

When we drove away, he was sitting on his haunches on the gravel in front of the store’s double front doors. I watched him in the rearview mirror and Virginia waved goodbye through the open passenger window. The last I saw of him he was sauntering into the high Meigs County grass.

Ed Staskus posts stories on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Cleveland Daybook http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”