By Ed Staskus

The morning Arunas Petkus and I left for California 2500-some miles from Cleveland, Ohio, the Summer of Love was a few years over. It had been a phenomenon in 1967 when as many as 100,000 people, mostly young, mostly hippies, converged on the neighborhood of Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco, hanging around, listening to music, dropping out, chasing infinity, and getting as much free love as they could.

We were both in high school at the time and stumbled into the 1970s having missed the hoopla. The Mamas & the Papas released “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)” and it got to number four on the Billboard Hot 100. It stayed there for a month, a golden oldie in the making, while the parade across Golden Gate Bridge went on and on. The vinyl single sold more than 7 million copies worldwide.

Arunas found a bucket of bolts, a 1958 VW Karmann Ghia, somehow got it running, brush painted it parakeet green, and was determined to hit the open road to see what all the excitement had been about. He also wanted to visit the spot at Twin Peaks where Chocolate George’s ashes had been scattered.

George Hendricks was a Hells Angel who was hit by a car while swerving around a stray cat on a quiet afternoon in as the Summer of Love was winding down, dying later that night from his injuries. He was known as Chocolate George because he was rarely seen without a quart of his favorite beverage, which was chocolate milk, usually spiked with whiskey. He was a favorite among the hippies because he was funny and friendly. His goatee was almost as long as his long hair, he wore a pot-shaped helmet when riding his Harley, and his denim vest was dotted with an assortment of tinny pin badges.

One of the badges said, “Go Easy on Kesey.” The writer Ken Kesey had been the de facto head of the Merry Pranksters. Much of the hippie aesthetic can be traced back to them and their Magic Bus. Arunas was an art student and liked the way the bus was decked out.

The Karmann Ghia was a two-door four-speed manual with an air-cooled 36 horsepower engine in the back. The trunk was in the front. Unlike most cars it had curved glass all the way around and frameless one-piece door glass. My friend’s rust bucket barely ran, unlike most of the sporty Karmann Ghia’s on the road, but it ran. There was still some magic left in it.

When Arunas asked me if I wanted to join him, I signed up on the spot. The two of us had gone to the same Catholic boy’s high school and were both at Cleveland State University. We threw our gear and backpacks in the front trunk of the car, sandwiches, apples, and pears in what passed for a rear seat, a bag of weed in the glove compartment, and waved goodbye to our friends at the Plaza Apartments.

The Plaza was on Prospect Ave., on the near east side, near Cleveland State University. It was an old but built to last four-story apartment building. Secretaries, clerks, college students, bohemians, bikers, retirees, and musicians lived there. Arunas was still living with his parents in North Collinwood, while I was a part-time undergraduate and part-time manual laborer trying to keep my head above water in a one-bedroom on the second floor.

We got almost as far as the Indiana border before an Ohio State Highway Patrolman stopped us. “Where do you think you’re going in that thing?” he asked after Arunas showed him his driver’s license. He wrinkled his nose looking at the car’s no-primer paint job.

“California.”

“Do you know you’re burning oil, lots of it?”

We knew that full well. That was why we had a case-and-a half of Valvoline with us. We had worked out the loss of motor oil at about a quart every two hundred miles and thought our stockpile would get us out west before the engine seized up.

“All right, either get this thing off the road or go back to Cleveland,” the patrolman said, waving us away with his ticket book.

On the way back home, we decided to go to Kelly’s Island, since we had sleeping bags and could more-or-less camp out, staying under a picnic table in case of rain. We took the Challenger ferry out of Sandusky, leaving the Kharmann Ghia behind. We landed at East Harbor State Park and stayed here until the end of the week. There were a campground, beach, and trails at the park, which were all we needed. We bought homemade granola and a couple gallons of spring water at a small store and settled down on a patch of sunshine. We met some high-class girls from Case Western Reserve University and played volleyball with them.

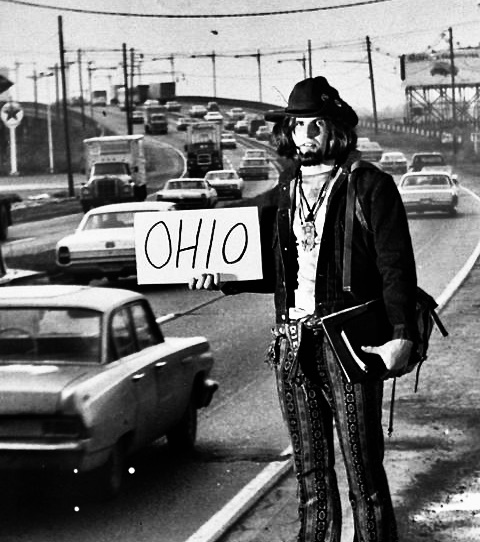

When we got back to Cleveland everybody marveled at our quick turnaround from the west coast and attractive tans. “We didn’t actually make it to California,” we had to explain to one-and-all. “We didn’t even make it out of Ohio.” We had to endure many snarky comments. When Virginia Sustarsic, one of my neighbors at the Plaza, said she was going to San Francisco and invited me to try again, joining her, I jumped at the chance. My feet got tangled up coming down when she said she was hitchhiking there.

“You’re going to thumb rides across the country?”

“Yes,” she said, in her detached but friendly way. She was a writer, photographer, and cottage craftsman. Virginia was a raconteur when she wanted to be one. She made a living dabbling in what interested her. She lived alone. Her boyfriend was an unrepentant beatnik.

“How about getting back?”

She explained she had arranged a ride as far as Colorado Springs. She planned on going knockabout the rest of the way, stay a week-or-so with friends on the bay, and hitchhike back. When I looked it up on a map, she was planning on hitchhiking four thousand-some miles. I didn’t know anything about bumming my way on the highway. When I asked, she confessed to having never tried it.

Our ride to Colorado Springs was a guy from Parma and his girlfriend in a nearly new T2 Microbus. Although it was unremarkable on the outside, the inside was vintage hippie music festival camper. It was comfortable and stocked. We stopped at a lake in Illinois and had lunch and went for a walk. I veered off the path and got lost, but spotted Virginia and our ride, and cut across a field to rejoin them. I tripped while running, fell flat on my face, but was unhurt.

We got to Colorado Springs in two days. The next day I found out what I had fallen into in Illinois was poison ivy. An itchy rash was all over my calves, forearms, and face. I tried Calamine lotion, but all I accomplished was giving myself a pink badge that said, ‘Look at me, I’m suffering.’” Virginia’s friends where we were staying let me use their motorcycle to go to a clinic. The doctor prescribed prednisone, a steroid, and by the time we got to San Francisco I was cured.

In the meantime, leaving the clinic, since it was a warm and sunny summer day, I went for a ride on the bike, which was a 1969 Triumph Tiger. I rode to the Pikes Peak Highway, 15 miles west, and about half the way up, until the bike started to dog it. What I didn’t know was at higher altitudes there wasn’t enough air for the carburetor. By that time, anyway, I had gotten cold in my shorts and t-shirt. It felt like the temperature had dropped thirty degrees. I turned around and rode down. There was a lot of grit and gravel on the road. I rode carefully. The last thing I wanted to happen was to dump the bike. I found out later that Colorado snowplows spread sand, not salt, in the winter.

All the way back to town, as dusk approached, I saw jumbo elk deer and walloping antelope. Even the racoons were enormous. I stayed slow and watchful, not wanting to bang into one of the beasts. We stayed a few days and hit the open road when my rash was better. There was no sense in scaring anybody off with my pink goo face. We had a cardboard sign saying “SF” and finally hit the jackpot when a tractor trailer going to Oakland picked us up.

The Rocky Mountains, left behind when the glaciers went back to where they came from, were zero cool to see, although I wouldn’t want to be a snowplow driver assigned to them. The weather was fair but cold with a high easterly wind the day we crossed them. Every switchback opened onto a panorama.

Virginia’s friends in San Francisco lived in Dogpatch, which was east of the Mission District and adjacent to the bay. It was a working class partly industrial partly residential neighborhood. They lived in a late nineteenth century house they were restoring. They went to work every day while we went exploring.

We stayed away from downtown where there was an overflow of strip clubs, peep shows, and sex shops. Skyscrapers were going up, there were restaurants, offices, and department stores, but it still looked like the smut capital of the United States. Elsewhere, rock-n-roll, jazz fusion, and bongo drums were in the air, especially the Castro District and Haight-Ashbury. Dive bars seemed to be everywhere.

Virginia went to Golden Gate Park and took pictures of winos, later entering one of them in a show at Cleveland State University. She had a high-tech 35mm Canon. When her photograph was rejected with the comment that it was blurry, she said, “That was the point.” I went to Twin Peaks and took a picture of the spot where Chocolate George’s ashes had been strewn. When Arunas saw it later on, he said there wasn’t much to see. I showed him some pictures from the summit facing northeast towards downtown and east towards the bay. “Those are nice,” he said, being polite. My camera was a Kodak Instamatic.

Twin Peaks is two peaks known as “Eureka” and “Noe.” They are both about a thousand feet high. They are a barrier to the summer coastal fog pushed in from the ocean. The west-facing slopes get fog and strong winds while the east-facing slopes get more sun and warmth. The ground is thin and sandy. George was somewhere around there..

We stayed for more than a week, riding Muni city busses for 25 cents a ride. No matter where we went there seemed to be an anti-Vietnam War protest going on. We rode carousel horses at Playland-at-the-Beach and went to Monkey Island at the zoo. We ducked into Kerry’s Lounge and Restaurant to chow down on French fries. We stayed away from all the Doggie Diners. We listened to buskers singing for tips at Pier 45 on Fisherman’s Wharf. Jewelry makers were all over the place. Virginia was on Cloud 9, being an artisan herself.

When we saw “The Human Jukebox” we went right over. Grimes Proznikoff kept himself out of sight in a cardboard refrigerator box until somebody gave him a donation and requested a song. Then he would pop out of the front flap and play the song on a trumpet. I asked him to play “Stone Free,” but he played “Ain’t Misbehavin’” instead.

“I don’t know nothing about Jimi Hendrix,” he said.

Everywhere we looked almost everybody was wearing groovy clothes made of bright polyester, which looked to be the material of choice. Tie-dye was on the way to the retirement home. Virginia dressed in classic hippie style while I dressed in classic Cleveland-style, jeans, t-shirt, and sneakers. I didn’t feel out of place in San Francisco, but I didn’t feel like I belonged, either. There were no steel mills and too many causes to worry about.

When we left, we started at the Bay Bridge and got a ride right away. By the time we got to the other end of the bridge the man at the wheel had already come on to Virginia. We asked him to drop us off. When he stopped on the shoulder and I got out of the back seat, he pushed Virginia out the passenger door, grabbed her shoulder bag, and sped away. She didn’t keep her traveling money in it, but what did he know? We saw the bag go sailing out the car window before he disappeared from sight and retrieved it. We smelled a brewery on the breath of the next driver and turned him down. After that a pock-marked face stopped and asked us if we were born again. When I said I had been raised a Catholic, he cursed and drove off.

We liked talking to the people who gave us rides but avoided talking about race, religion, and politics. I carried a pocket jackknife but wasn’t sure what I would do with it if the occasion ever arose. We never hitchhiked once it got dark, because that was when lowlifes and imbeciles were most likely to come out.

We went back the way we had come, to Nevada, through Utah, Nebraska, and Iowa to Chicago, and returning in the middle of the day to the south shore of Lake Erie. We thumbed rides at entrances to highways, at toll gates, and especially at off-the-ramp gas stations whenever we could. Gas stations were good for approaching people and asking them face-to-face if they were going our way.

One of the best things about hitchhiking is you can take any exit that you happen to feel is the right one. One of the worst things is running into somebody who says, “I can tell you’re not from around these parts.” We avoided big cities because getting out of them was time-consuming. We avoided small towns because we didn’t want to be the new counterculture archenemies in town. We got lucky when a shabby gentleman in a big orange Dodge with a cooler full of food and drink in the back seat picked us up outside of Omaha on his way to Kalamazoo. He listened to a border blaster on the radio all the way. We ate the sandwiches he offered us.

Our last ride was in an unmarked Wood’s County sheriff’s car. He picked us up near Perrysburg on his way to Cleveland’s Central Police Station to pick up a criminal. It was the same station where Jane “Hanoi Jane” Fonda was put behind bars a couple of years earlier. She was famous and not a real criminal and so didn’t stay long.

“They said they were getting orders from the White House, that would be the Nixon White House,” she said about the arrest. “I think they hoped the ‘scandal’ would cause my college speeches to be canceled and ruin my respectability. I was handcuffed and put in jail.” The day she was arrested at Cleveland Hopkins Airport, she pushed Ed Matuszak, a special agent for the U. S. Customs Bureau, and kicked Cleveland Policeman Pieper in a sensitive place.

The city policeman later sued Jane Fonda for $100,000 for the kick that made him “weak and sore.” The federal policeman shrugged off the shove. The charges and suit were eventually dropped.

The Wood County sheriff was a friendly middle-aged man who warned us about the dangers of hitchhiking and drove us to near our home. When we got out of the car, he gave us ten dollars. “Get yourselves a square meal,” he said. We walked the half dozen blocks to the Plaza, dropped off our stuff, and walked the block and half to Hatton’s Deli on East 36th St. and Euclid Ave. where Virginia worked part-time. There was an eight-foot by eight-foot neon sign on the side of the three-story building. It said, “Corned Beef Best in Town.” We had waffles and scrambled eggs.

The waitress lingered at our table pouring coffee, chatting it up while we dug into apple pie. We split the big slice. The butter knife was dull, so I used my jackknife. She asked how our cross-country trip had gone. I gave her the highlights while Virginia went into details. When the waitress asked why we hadn’t gone Greyhound, Virginia smiled like a cat, but I put my cards on the table.

“I had an itch to go and the stone free way was the way to go.”

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street at http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”

“Bomb City” by Ed Staskus

“A police procedural when the Rust Belt was a mean street.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Cleveland, Ohio 1975. The John Scalish Crime Family and Danny Greene’s Irish Mob are at war. Car bombs are the weapon of choice. Two police detectives are assigned to find the bomb makers. It gets personal.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication