By Ed Staskus

When Frank Gwozdz and Tyrone Walker sat down in front of Lieutenant Ed Kovacic’s desk, Tyrone had a thick sheaf of files with him. Their ranking officer behind the desk looked at them. Tyrone looked at his ranking officer. Frank looked at the windows. It was windy and raining hard. The Central Station wasn’t what it used to be. Frank watched rain leaking in through the windows. He believed in keeping the out of doors where it belonged, which was out of doors. It wasn’t his problem, though. The city’s solution to problems was often as bad as the problem. He turned his attention back to the matter at hand.

“These are files of all the bombings the past five years in northeast Ohio, including the Youngstown bombings, which are almost as everyday as ours,” Tyrone said. Youngstown had long since been dubbed “Crime Town USA” by the Saturday Evening Post. Their gang wars had been going on as long as those in Cleveland.

“You can keep those on your lap for now, son,” Lieutenant Kovacic said. “Never mind about northeast Ohio. Forget about Youngstown. Concentrate on Cleveland.” A close second to Tyrone not liking being called nigger was not liking being called son. He did a slow burn but didn’t say anything. Saying something would have been a mistake. He bit his tongue.

Ed Kovacic wasn’t born a police officer. He was born a Slovenian and baptized at St. Vitus Catholic Church, but everybody knew he was going to die a police officer. When he did the funeral mass was going to be at St. Vitus. Whenever anybody called him a cop, he reminded them with a stern look that he was a police officer. He hardly ever had to say it twice. When he did have to say it twice, his fellow police officers took a step away from whoever had called him a cop one too many times.

“We don’t mind the Irish and Italian mobs blowing each other up, it keeps our cells spick and span, but they’ve started killing bystanders,” he said. “We can’t stand for that, which is why we are adding men to this investigation.”

When Ed Kovacic graduated the police academy the first assignment he had was to walk a beat in the 6th District. He worked his way up to the Decoy Squad, the Detective Bureau, and finally the Bomb Squad. He married his high school sweetheart in 1951 before shipping off to the Korean War. When he got back he and his wife got busy in bed making six children. After that his wife stayed busy raising them. They lived in North Collinwood.

“We want to get them before they get more civilians. That’s your number one job from now on. When you’ve got the goods on one of them report to me. Make sure the charges are tight as a drum so we don’t wind up wasting our time. If you apprehend somebody red-handed, do what you have to do. Try to get him back here in one piece so we can question him.” He gave his police detectives a sharp look.

“Are we clear about that?”

“Yes, sir,” Tyrone said. He knew his rulebook inside and out. Frank nodded. He had his own rule book spelling out what one piece meant. It meant still breathing.

“The first thing I want you to do is go over to Lakewood. I talked to the chief there and he’s expecting you. After you see him, I want you to find Richie Drake and find out what he knows, or at least what he’s willing to tell you. He’s one of our on-again off-again informers. He’s a west side man. I understand he spends most of his life at the Tam O’Shanter there in Lakewood.”

“I know the man and I know the place,” Frank said. He knew every stoolie in town, just like he knew every bar on every side of town that served food and drink to wrongdoers.

“Which reminds me, the Plain Dealer boy who saw it happen, his father called, said the boy has something to tell us. Here’s the address.” He handed Frank a slip of paper. “Stop there while you’re on that side of town and find out what he has to say.”

Lakewood City Hall, its courtroom, and the police department, were on Detroit Ave., closer to Cleveland than the rest of the near west side suburb. Frank parked in the back. He and Tyrone went inside and waited. When they met with the police chief there wasn’t much he could tell them, other than to say his department would do all it could do to help.

“We believe in law and order here,” he said. “You point them out, we’ll lock them up.”

Lakewood’s first jail was in the Halfway House, which was a bar on Detroit Ave., in one of the back rooms that had a locking door. It was soon relocated to a barn where lawbreakers were kept in two steel cages. After that they were kept in the basement of a sprawling house at the corner of Detroit Ave. and Warren Rd.

After World War One Lakewood’s main streets, like Detroit Ave. and Clifton Blvd., began to be paved. When they were, speeding problems surfaced. The police force grew, adding two motorcycle men, to patrol Clifton Blvd. and Lake Ave., the streets where the better half lived. A Friday Night Burglar plied his trade on those streets, forcing the police to work overtime while those they were protecting were out on the town. The burglar was never caught. The better half bought more valuables to replace those that went missing.

When Frank and Tyrone walked into the Tam O’Shanter the late afternoon crowd was starting to fill it up. They made their way to the bar. The bartender asked them what they would have.

“Don’t I know you?” Frank asked.

Jimmy Stamper was the bartender. “Maybe, but I don’t know you,” he said, wiping his hands with a damp rag.

“Are you in a band?”

“I’m a drummer, been in plenty of bands,” Jimmy said.

“Are you in a band called Standing Room Only.”

“You have a good memory,” Jimmy said. “That would have been around 1969, maybe 1970. It sounds like you liked our sound.”

Frank didn’t tell Jimmy he had been tailing a suspect who was at a bar the band was playing at. The man stayed there until closing time which meant Frank stayed there until closing time. Surveillance was the easiest but most time-consuming part of his job. He had never liked rock and roll and after that night he disliked it even more. Standing Room Only played rock and roll covers. The only one Frank liked was their cover of the Venture’s tune “Hawaii Five-O.”

“We’re looking for Richie,” Frank said, flashing his badge just long enough for Jimmy to get a peek of it. The bartender hitched his thumb over his left shoulder. “Last booth over there by the men’s toilets. He’s got a blonde with him. He should still be sober. At least he’s still doing all the sweet talking.”

Frank sat down on the other side of Richie Drake after giving the blonde the thumb. “Drift” is what he said to her. She sat at the bar sulking. Tyrone stood to the side, neither near nor far, but close enough so that Richie knew he was between him and the door. Pinball machines and their pinball wizards were making a racket opposite the booth.

“What can I do for you?” Richie Drake asked. He didn’t bother asking who they were.

Somebody slid a dime into the Rock-Ola jukebox. “It’s just your jive talkin’, you’re telling me lies, yeah, jive talkin’” the Bee Gees sang in their trademark falsetto style. Frank thought they sounded like pansies.

“That business last Sunday down the street,” Frank said.

“What business?”

“You can either tell me here or out back while my partner has a Ginger Ale.”

“Hold your horses,” Richie said. “Everybody knows it was the Italians.”

Why?”

“I don’t know, exactly, but it had something to do with the Irishman. The guy who got it was a bog hopper. They can’t get to the main man, but they got to him.”

“One more time, why?”

“So far as I know, it was a message more than anything else.”

“A message from who exactly?”

“The way I hear it, it was Jack White.”

Frank let it go at that. It seemed to him that Richie Drake didn’t know a hell of a whole lot. The police detective stood up and walked away. He stopped at the Rock-Ola jukebox and glanced at the playlist. He walked back to the booth. “I need a dime,” he said. Richie gave him a dime. He selected a song by B. J. Thomas. The juke box was playing the tune when he and Tyrone left.

“Hey, wontcha play another somebody done somebody wrong song, so sad that it makes somebody cry, and make me feel at home.”

Frank and Tyrone drove to Ethel Ave. They stopped and looked at Lorcan Sullivan’s corner house but didn’t bother getting out of the car. They drove to Tommy Monk’s house, parking across the street. Frank pressed the doorbell. When nobody answered they walked up the driveway to the backyard. The family was grilling out and having burgers and corn at a picnic table. A sweet gum tree kept them shaded. Chain link fencing and Japanese yews kept the yard private. Tommy’s father Einar invited them to sit down, bringing two lawn chairs out from the garage. Einar had changed the Old World family name but kept his given name. For all that, everybody and his wife called him Eddie.

“How did you know the man in the corner house?” Frank asked Tommy.

“I delivered his paper every day,” Tommy said. “I knew him better than most because he tipped me better than most.”

“Did you see anything before it happened?”

“No, it was like any other Sunday morning, except it wasn’t raining or snowing.”

“Did you see anything special after it happened?”

“No.”

“What is it you have to tell us?”

“Mr. Sullivan asked me to keep an eye out for anybody prowling our street who didn’t look right. He always gave me a big bonus at Christmas. He told me what to look for. I never saw anybody until yesterday. The man I saw was just like what Mr. Sullivan said he might be. I memorized his license plate.”

“What is it?”

“Wait a minute,” Tommy said. “I need a copy of the newspaper.”

He ran to the back door. A minute later he burst back through the door and ran to the picnic table. He had the front page of yesterday’s Cleveland Plain Dealer with him. He crossed out the headline and in its place wrote down the license plate number. He handed it to Frank.

“Are you sure this is the number?”

“I never make a mistake whenever I memorize anything this way.”

“Good work, son,” Frank said. “If you see that man again, be careful. Don’t draw any attention to yourself. Tell your father right away.”

He gave Eddie Monk his number. “Call me if your son spots anything else. I don’t think there’s any danger to him, but you never can tell. Make sure he knows not to talk to strangers.”

“All my children already know that,” Eddie Monk said.

“Good,” Frank said.

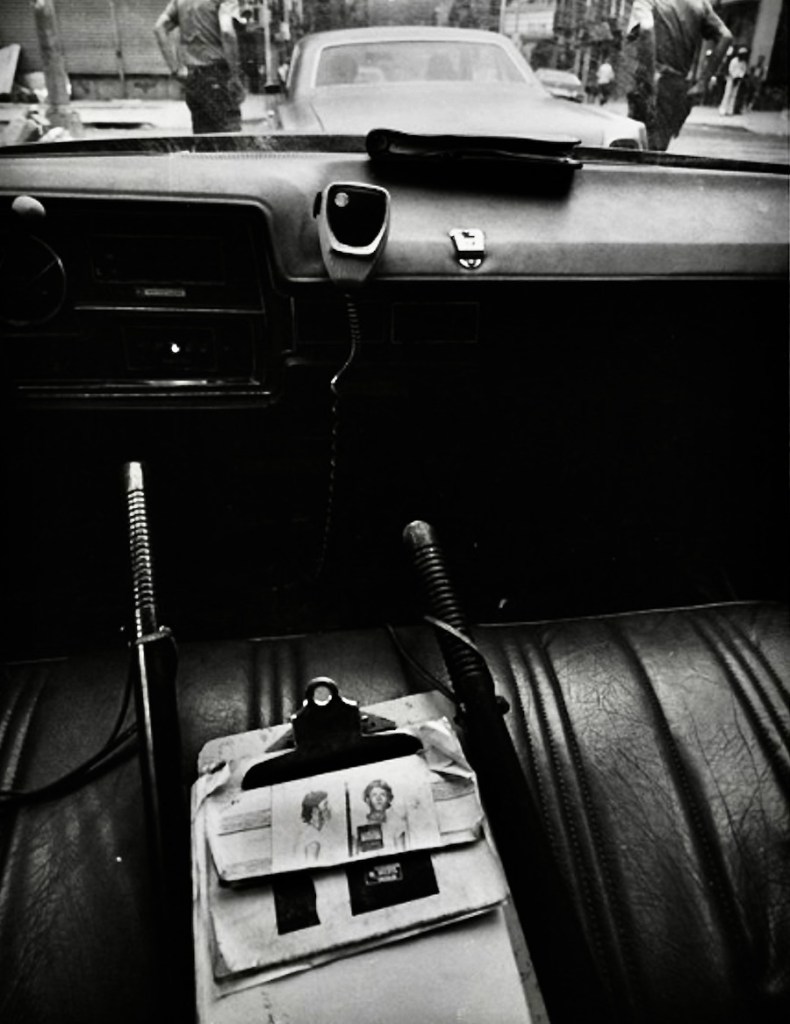

The police detectives walked back to their car. Tyrone called in the license plate number. Frank smoked a cigarette while they waited. Tyrone had already formed the impression Frank wasn’t big on small talk. He seemed to keep most talk to himself. When they got the license plate’s street address, Tyrone wrote it down and handed it to his partner.

“That’s in South Collinwood,” Frank said. “Let’s go there and pay Earnest Coote a visit.”

Excerpted from the crime novel “Bomb City.”

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com.

“Bomb City” by Ed Staskus

“A police procedural when the Rust Belt was a mean street.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Cleveland, Ohio 1975. The John Scalish Crime Family and Danny Greene’s Irish Mob are at war. Car bombs are the weapon of choice. Two police detectives are assigned to find the bomb makers. It gets personal.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication